“Water is going to be hauled from Missouri to arid Western Kansas.”

Groundwater Management District 3, in southwestern Kansas, has received a permit from water authorities to haul water for dry cropland.

“It’s designed to prove large-scale movement of water could help keep the Ogallala Aquifer from drying up,” district manager Mark Rude said.

About 6,000 gallons of water will be siphoned from the Missouri River and hauled about 400 miles costing approximately $7,000.

“Half of it will be poured onto Wichita County farmland,” according to Allison Kite of the Kansas Reflector. “Remainder of the water will be hauled into dry eastern Colorado.”

“It’ll basically be moving water from where it’s in excess to where it’s in short supply,” Rude clarified.

Other groundwater management officials say it’s a distraction from the far more urgent task of conserving Western Kansas water

“For one, it’s a waste of water,” said Shannon Kenyon, manager of Groundwater Management District 4 in northwest Kansas.

“Their idea, instead of telling producers, ‘You must cut back,’ is to just dump water on dryland Kansas,” Kenyon evaluated.

“The Ogallala Aquifer, America’s largest underground reservoir, has been in decline for decades,” Kenyon pointed out. That’s since farmers started pumping the underground water to irrigate crops following World War II.

“Some parts of the aquifer have half the water than before irrigating from them began,” Kenyon tallied. “In some areas, there’s only about 10 years of water left.”

Loss of the aquifer would fundamentally alter life in western Kansas and destroy farmers’ livelihoods, Kite predicted.

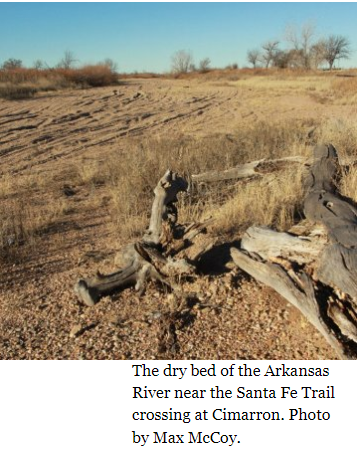

“There’s little surface water since streams that reliably flowed through the area in 1961 all but disappeared,” according to the Kansas Geological Survey.

Naysayers claim climate change will lower farm belt yields “as soon as 2030.”

Officials have pursued a number of strategies to help the aquifer including asking farmers to sign agreements to reduce usage.

It has been suggested to equip farmers with underground moisture probes to help them water their crops more conservatively.

Hauling water long distance attempts to prove that transferring water from where it’s plentiful or from flooded areas is feasible.

One such idea is known as the Kansas Aqueduct. “It would pump water uphill from the Missouri River at Kansas’ eastern border to western Kansas,” Rude explained.

There are no formal efforts underway to make the longshot project a reality, Rude said. However, the district has an idea that he has previously recommended to the Kansas Legislature in the past.

Going through the regulatory process trucking water across the state helps officials through the process in preparation for larger projects.

“You take steps, evaluate, and learn,” Rude said. “This proof of concept is part of that process for the Kansas Groundwater Management District 3.”

Earl Lewis, chief engineer who signed the permit, said he didn’t see the project comparable to a larger water transfer.

“Hauling 6,000 gallons of water across the state happens all the time,” Lewis added.

Kansas House Rep. Lindsay Vaughn, D-Overland Park, called it a “political stunt.”

“For the sake of the state, I hope Groundwater Management District 3 starts taking its responsibility seriously,” she said. “Time is running out.

Groundwater Management Districts 1 and 4, near the Colorado border, are taking different approaches to saving the Ogallala. “Western Kansas needs to focus on conserving water now while an aqueduct could take decades to get off the ground,” Kenyon repeated.

Groundwater Management District 1 chose not to participate in the project, said Katie Durham, district manager. However, the Wichita County farm that will receive 3,000 gallons of water lies in District 1.

“I think it’s always smart to look for projects that could help in the future,” Durham said. “But it’s also important to manage the resources you have addressing the Ogallala decline and protecting local communities.”

Districts 1 and 4 have established local enhanced management to enforce reductions in groundwater use.

“Our district is conserving water by providing information to well owners on the amount they’ve pumped from the aquifer,” Rude said. “They can compare with their neighbors about how they’re affecting the long-term health of the aquifer.

“That information is key in voluntary conservation efforts and discussing collective limits to further conserve the groundwater supply,” Rude said.